In the daily notes I jotted down during a trip last Fall to Cambridge, Massachusetts, I mentioned a visit to Harvard’s Fogg Art Museum. There I encountered a couple of pieces by the artist Sol LeWitt that captivated me. Since the time that I transcribed my journal pages from that trip, I have been thinking about LeWitt’s art. I think about those pieces as I drink a morning cup of coffee and glance across the room at a blank white wall; as the lines on the road telegraph by the windows of my truck like so many dots and dashes; as I glide above the patterns of square tiles on the bottom of the swimming pool; as I lie in bed staring at the slowly shifting shapes of light on the ceiling, sifting through the window blinds. I felt compelled to find out more about LeWitt.

Sol LeWitt was an American artist who lived and worked from 1928 to 2007. During an earlier period, LeWitt’s work might have been considered Abstract but, since he was an artist not necessarily given to creating work randomly, he chose to consider his works Conceptual. He created drawings, paintings and sculptures (which he called “structures”). The basis for much of his work was geometric forms, quite a few of them based on the cube. His work is non-narrative; for instance, there are no human forms present, there is no traditional story or tableau being expressed. Yet, his works do not feel static. There is an intelligence and wit about them that is slyly engaging, as if the artist is challenging the viewer to see that a cube can represent more than just a figure with six sides, that it has potential beyond mere stacking and storage.

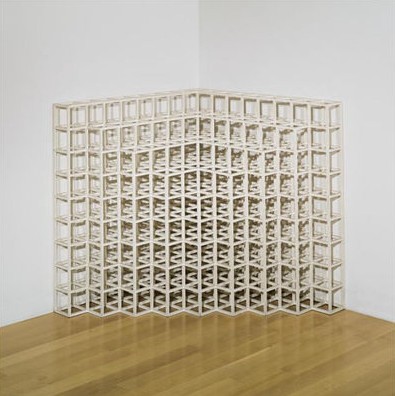

Corner Piece No. 2 (from Cube structures based on nine modules) (2001)

[painted wood]

In a Yale University Press publication that accompanied a 2000 exhibition of LeWitt’s work, the artist attempted to verbalize the philosophy behind his art. Some of his statements seem contradictory at first, but he seems to be begging a fresh way to look at artistic expression:

I will refer to the kind of art in which I am involved as conceptual art. In conceptual art the idea or concept is the most important aspect of the work. When an artist uses a conceptual form of art, it means that all of the planning and decisions are made beforehand and the execution is a perfunctory affair. The idea becomes a machine that makes the art. This kind of art is not theoretical or illustrative of theories; it is intuitive, it is involved with all types of mental processes and it is purposeless. It is usually free from the dependence on the skill of the artist as a craftsman. It is the objective of the artist who is concerned with conceptual art to make his work mentally interesting to the spectator, and therefore usually he would want it to become emotionally dry. There is no reason to suppose however, that the conceptual artist is out to bore the viewer. It is only the expectation of an emotional kick, to which one conditioned to expressionist art is accustomed, that would deter the viewer from perceiving this art.

Wall Drawing No. 146 (1972)

[blue crayon]

In 1969, LeWitt summarized his thoughts on his art in a series of statements, titled simply “Sentences on Conceptual Art.” They are succinct and witty, and a sturdy set of guiding principles for both artist and spectator. I found that I violated at least one of them (#18) when I first encountered LeWitt’s work that day at the Fogg.

My advice: read each one, turn it over in your head, think of an application where it might apply – perhaps as it relates to some piece of art you have seen and admire, or a public work of art or architecture that you pass by on a daily basis.

- Conceptual artists are mystics rather than rationalists. They leap to conclusions that logic cannot reach.

- Rational judgements repeat rational judgements.

- Irrational judgements lead to new experience.

- Formal art is essentially rational.

- Irrational thoughts should be followed absolutely and logically.

- If the artist changes his mind midway through the execution of the piece he compromises the result and repeats past results.

- The artist’s will is secondary to the process he initiates from idea to completion. His wilfulness may only be ego.

- When words such as painting and sculpture are used, they connote a whole tradition and imply a consequent acceptance of this tradition, thus placing limitations on the artist who would be reluctant to make art that goes beyond the limitations.

- The concept and idea are different. The former implies a general direction while the latter is the component. Ideas implement the concept.

- Ideas can be works of art; they are in a chain of development that may eventually find some form. All ideas need not be made physical.

(“Sol LeWitt’s Sentences on Conceptual Art” continued)

0 responses so far ↓

There are no comments yet...Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment